Remarkably Thoughtful

Erfurt II

A different, not necessarily enjoyable page of the state capital is to be opened. It won’t be the big, eye-catching sights. But to simply overlook and ignore them, they shape the inner and outer cityscape too concisely.

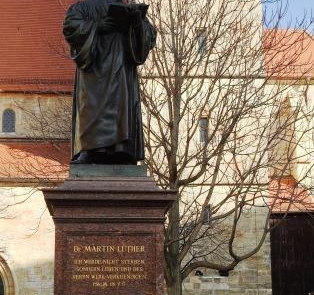

We start our little city walk again at the Anger with its merchant church. Their actual origin cannot be clearly proven. Was it Frisian traders who laid the foundation stone as early as the 8th century AD, or should we assume that they were built in the High Middle Ages (11th to 13th centuries)? Science is still puzzling. In contrast, it is documented that the parents of Johann Sebastian Bach were married in it in 1668. It is also documented that Martin Luther preached in this church on October 22, 1522 (see memorial plaque on the church wall) and thereby settled a denominational dispute. The Luther statue in front of the church is also a visual reminder of Luther’s ten uninterrupted years in Erfurt. As a student, he enrolled at the Erfurt University (one of the oldest universities in Germany) for the summer semester of 1501, and stayed there as a student at the artist faculty of the “seven liberal arts” until 1505 with a “Magister Artium”. Only then did he turn to studying theology, when he entered the Augustinian Hermitage in Erfurt. In the first place, these two stages in life were not decisive for the erection of a monument, because at that time the religious world did not yet know it. Rather, his later reformatory actions gave him the reputation that still carries him today. “His upright posture as shown, an open Bible on his left hand, the right one, as it were, pointing to the text, looking into the distance (future?) with a thoughtful look, should reflect Luther’s courage to confess, his steadfastness in faith and his determination to work in the Reformation” . At least that is the explanation of the sculptor of the Luther statue, Prof. Fritz Schaper. Another monument, which we find on the fish market a few streets further in the direction of Domplatz, can also have a remarkably thoughtful effect. Is it a “Roland” or a “Römer”? Figure, equipment, armament clearly indicate a “Roman”.However, Erfurt’s coat of arms is emblazoned on his shield and flag. So “Roland” as a symbol of (imperial) freedom after all? Without losing ourselves too deeply in the city’s history, perhaps it helps with the decision that Erfurt, predominantly in the 16th century, was part of the city of Mainz and the Mainz diocese, that earlier (from 1448) the statue of ” Saint Martin ”, i.e. the patron saint of Mainz, was torn down in 1525 during a revolt against Mainz and was only re-erected in its present, restored form in 1591 as“ Römer ”. He must have been a brave rascal to create the artist of this statue, the Dutch sculptor Israel von Milla, namely the patron saint and rule symbolism “Saint Martin” as a Roman soldier fighting for freedom and independence. “Honte y soit qui mal y pense” (shame on those who think badly): Couldn’t the “Roman Roland” also be understood as a call for liberation from the rule of Mainz? Perhaps not only remarkable but also thought-provoking. No memorial, but unforgettalbe: Willy Brandt’s trip to Erfurt on March 19, 1970. The first notable summit meeting of two German heads of government represented the beginning of a German-German rapprochement. We remember the cheers of the Erfurt population when Willy Brandt waved to himself from his hotel “Erfurter Hof”, politics from the hotel window. If you want to empathize with this thought-provoking encounter, go to the main train station. The call “Willy Brandt to the window” mounted on the hotel roof (today the Sparkasse) cannot be overlooked. At several locations in ERFURT, we come across sites that make us think. What they have in common is that they all contain “Jewish life in ERFURT”, past and present. If you want to start again on the Anger, you will find depressing traces of past Jewish life here. So-called “stumbling blocks” as a reminder of Nazi victims are well known. Small brass plaques with names in front of the respective last homes of the victims are set in the sidewalks as a reminder. In ERFURT these memorials are called “commemorating needles”. Decentralized, spread over the whole city, the Erfurt victims of the Shoa (= National Socialist genocide of the Jews of Europe) remain alive in our consciousness. To a Mrs. Spier (murdered in 1942 in Auschwitz) and her husband Carl Ludwig (died on the death march in 1945), for example, refer the “commemorating needle” with a biogram on Anger no. 46. Another with the inscription “Günther Beer (Ghetto Belzyce)” was set up at 23 Domplatz. Eight such commemorative needles can be hiked. With the excellent tram network you can at least cover longer distances. The Krämerbrücke is a tourist magnet on the one hand and a historical memorial on the other. The memorial stone for a MIKWE is not on the bridge itself but a little away from it, where the Krämerbrücke spans the Gera. This Jewish ritual bath was only rediscovered in 2007. In addition to the synagogue and cemetery, such a ritual immersion bath is one of the most important facilities of a Jewish community. This small sight is definitely worth a walk with a photo stop, also to be able to enjoy the colorful house fronts (rear) of the Krämerbrücke. Hidden in the maze of alleys in Erfurt’s old town (Waagegasse 8), we enter the “Old Synagogue”. Its oldest components date back to the 11th century. Inside, the museum exhibits particularly illustrate the way of life of the first Jewish community in ERFURT. In addition to the actual building history, the museum houses a synagogue treasure that is said to have been buried on the occasion of a pogrom in 1349. Hebrew manuscripts complement the presentations. Let us conclude this chapter with another remarkable memorial. It is officially called the “Andreasstrasse Memorial and Educational Site”. Behind it is the former MfS (Ministry of State Security) remand prison ERFURT. On the one hand, this museum is dedicated to the former political prisoners of the former GDR. A plaque on one of the prison walls indicates reasons for their imprisonment: “They wanted freedom and human dignity”. During a tour of the former prison building on the so-called detention floor, we immerse ourselves in the living conditions of the inmates. Selected examples also illustrate the surveillance system of the former GDR. Unyielding and oppositional behavior should not be missing. In short: This more than thought-provoking story of the “GDR legal system” is opened up in a way that is visually and mentally easy to understand.sequel follows Text: Wolf LeichsenringPhotos: Heike Lerch-Jankovicz

Wolf Leichsenring – Travel Journalist